Historic tariffs and tumult Trade policies tailored for purpose both hit and miss

By Steve Fairchild

Trade policies tailored for purpose both hit and miss

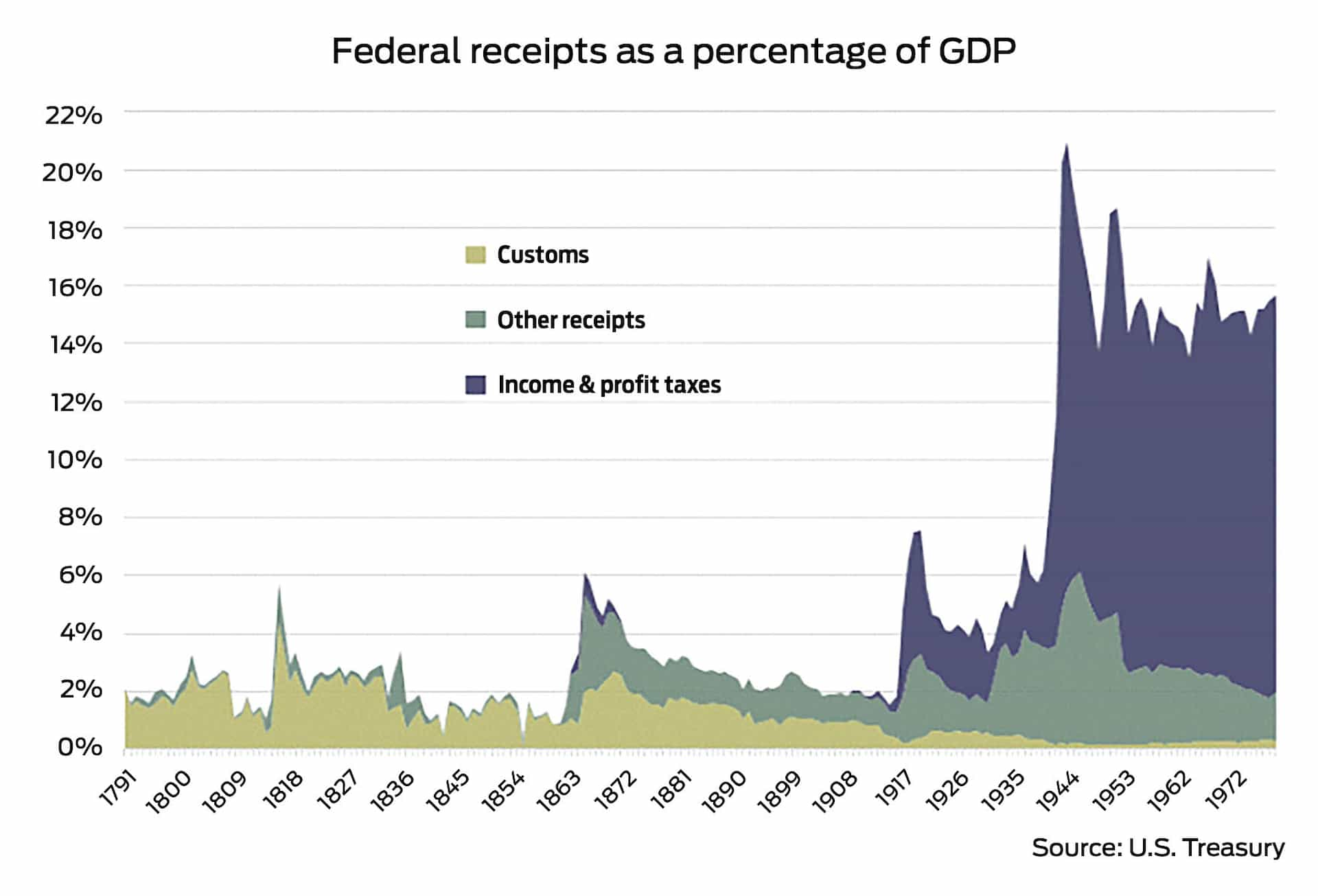

From its fledgling days as a nation to modern day, the U.S. government has employed tariffs as a means of controlling trade and extracting income from commerce. And for as long as the government has employed tariffs, we have argued about them. By their nature, tariffs often create winners and losers—the best ingredients for genuine conflict.

Looking over the past century or so of U.S. tariff activity, the goals have been revenue generation, protectionism and reciprocity to tariffs on our goods. Some hit and some missed, but all of them stirred debate. More often than settling tariff arguments on the principle of their utility, larger social and economic realities have been both midwife and undertaker for these plans.

Revenue to reform

From the nation’s inception through the late 1880s, tariffs were the main revenue source for the U.S. But after amassing a Civil War debt plus a couple of financial panics in the late 1800s, federal officials had begun to reconsider such a singular reliance. Enter the 1913 Underwood Tariff. About the same time farmers were rallying to form the farm clubs that would become MFA, President Woodrow Wilson was introducing ideas that would have long-lasting effects well beyond agriculture.

From the nation’s inception through the late 1880s, tariffs were the main revenue source for the U.S. But after amassing a Civil War debt plus a couple of financial panics in the late 1800s, federal officials had begun to reconsider such a singular reliance. Enter the 1913 Underwood Tariff. About the same time farmers were rallying to form the farm clubs that would become MFA, President Woodrow Wilson was introducing ideas that would have long-lasting effects well beyond agriculture.

The Underwood Tariff, championed by Wilson and enacted by Congress in 1913, marked a turning point for tariffs. Among Wilson’s promises to regulate banks and big business, lowering tariffs to promote competition had been a focus point. This act reduced average rates by about 15%, dropping from 40% to around 25%, and eliminated tariffs on importation of certain raw commodity materials as a way to bolster U.S. industry.

But perhaps more importantly, the act was tied to the 16th Amendment ratified earlier the same year, which codified a national income tax. This new income tax was a vehicle to replace lost revenue from the tariff move, which over time pushed tariffs away from a primary source of federal funding to more of a tool for policy.

It’s worth remembering that even though the U.S. was a net exporter of agricultural products in the late 1800s and early 1900s, horses and mules were still the main source of power on farms, and to fuel that power, a considerable amount of farm output was spent as feed. In 1899, about 52% of corn went into livestock and horses and just 22% was exported. Oats were still a major crop for that very reason with some 60% of the harvest used for fueling animals.

For Missouri farmers, the Underwood Tariff offered both opportunities and challenges. Lower costs for steel tools and machinery made production costs more affordable but domestic agriculture production grew more vulnerable to competition from imported commodities.

Tractors had been appearing on farms for a few years during this time, foreshadowing the radical change that would come as mechanization began to revolutionize American agriculture and how tariffs affected farmers. By the 1920s, land required to grow crops to feed mules and horses began to steadily shift to producing more grain sold off the farm, which gradually made producers more sensitive to import/export volatility.

When Wilson left office, several new tariff titles focused on a reversion to protectionism.

Depression lesson

Meanwhile, mechanization continued to change the landscape. In 1930, MFA’s member magazine, The Missouri Farmer (now Today’s Farmer), published multiple articles lamenting the decline of horse numbers in the state and debated horse-versus-tractor economics. Those debates were colored by more than the practicality of evolving to tractors. Depression had first taken agriculture and then the whole U.S. economy.

In reaction to severely depressed agricultural and industrial sectors, President Herbert Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in June 1930. The idea behind this new tariff was to protect domestic industries and agriculture from foreign competition. It raised tariffs from an average tax rate on imports of about 40% to 59.1% on some 20,000 imported goods, including wheat and corn.

The reason Smoot-Hawley makes the history books is that it didn’t go as planned. Historians argue about how much effect it had on the lingering depression of 1929, but it did elicit a strong response from major international trading partners with retaliatory tariffs against U.S. goods. The United States exported some $5.2 billion in 1929. By 1933, that total had fallen to $1.7 billion.

Open and closed

Smoot-Hawley became a cautionary tale highlighting the unintended consequences of protectionism. Successive iterations of 1947’s General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)—including the President Kennedy Round of the 1960s—further slashed tariffs. GATT, intended to reduce barriers and promote international trade, deepened the post-World War II era of trade liberalization that generally boosted U.S. agricultural exports. By 1970, U.S. farm exports had grown to $7 billion annually.

A notable exception to this era of fewer trade restrictions was the 1980 Russian grain embargo imposed by President Jimmy Carter. In January that year, as a response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Carter stopped grain sales to the then USSR. This action reversed momentum of the Trade Act of 1974, which had opened exports to the Soviets and generated large volumes of grain sales. The embargo was met by fierce resistance from the U.S. agricultural community, drawing parallels to the lessons of Smoot-Hawley.

While the goal of the embargo was to deliver a nonviolent response for an adversary’s military action, other grain-producing countries were quick to pick up the market share represented by the USSR’s purchases. U.S. growers were left with a surplus of grain, driving prices down and further complicating the 1980s agriculture economy and Carter’s ability to be re-elected.

The tariff moves of 2025 are too fluidly changing to make specific comments on these pages, but they have touched on all the themes of historic efforts—revenue generation, protectionism and reciprocity. Chinese electronics? Canadian lumber? U.S. hogs, soybeans, corn and beef? Among international trading partners and domestic economic constituents, this round of tariffs has delivered the ingredients for conflict. No one wants a bad deal.

***

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE JUNE/JULY ISSUE OF TODAY'S FARMER