Biological breakdown

By Allison Jenkins

MFA research helps producers sort hype from help in a crowded market

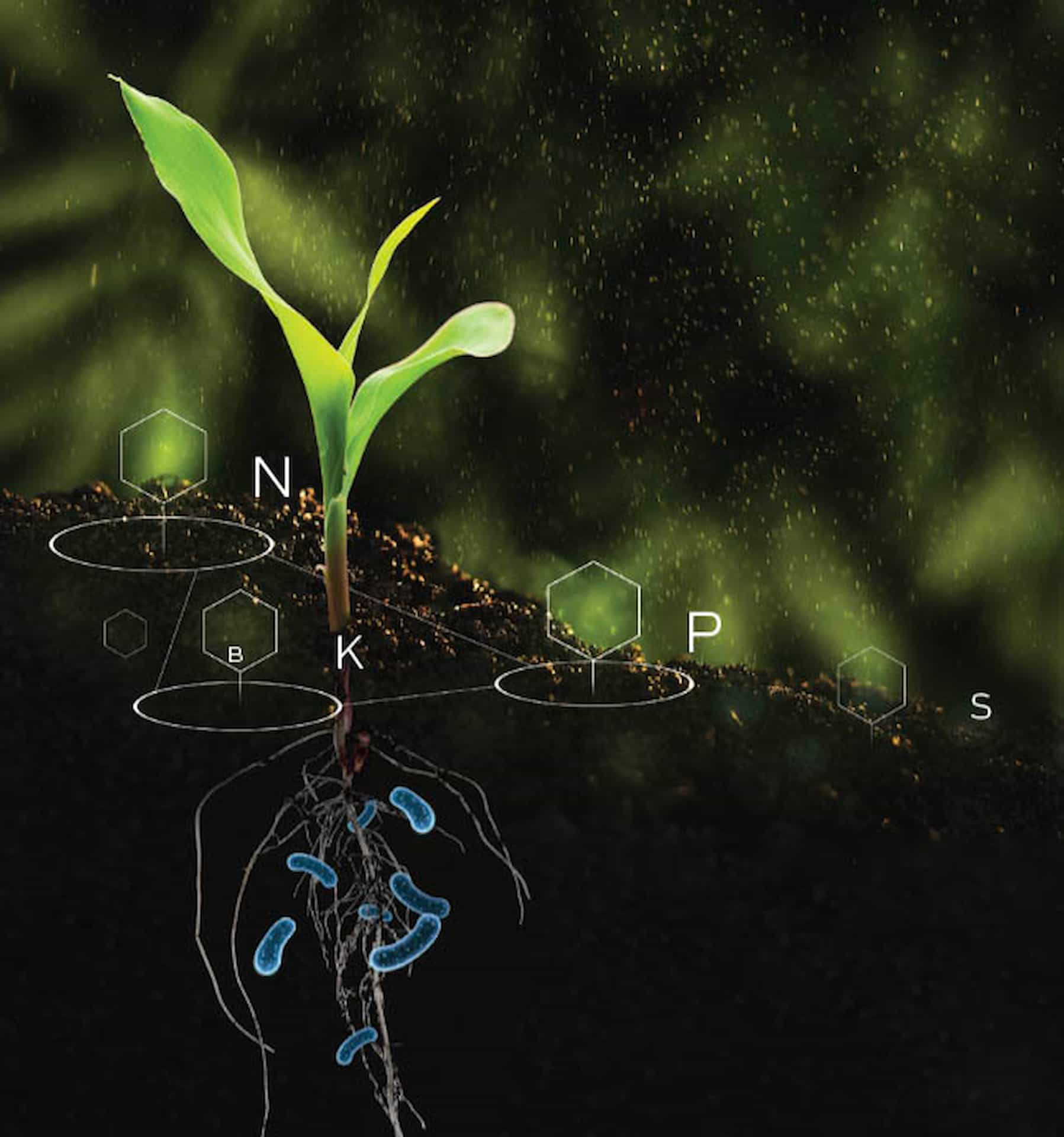

Biologicals have become one of the fastest-growing segments in row-crop inputs, but the term itself is anything but simple. Much like the word “sustainability” has different meanings in different situations, the word “biological” is an umbrella used to describe a wide range of products with very different functions and expectations. That’s why understanding the type of biological—and what problem it solves—is essential.

“Not all biological products are created equal, and each performs in a unique way, resulting in questions of which types work, where and how they work, and most importantly, what other management practices help realize the full economic benefit,” said Connor Sible, research assistant professor at the University of Illinois who has extensively studied biologicals in row-crop production. “Only with a proper understanding can you effectively place and use a product to optimize crop performance—and, just as importantly, know when not to use it.”

Applied directly to the seed, soil or crops, biological products are designed to enhance nutrient availability or help the plants manage stress, such as drought. The concept is not new, said Garrett Imhoff, MFA research agronomist. In fact, the natural nitrogen-fixing power of legumes such as alfalfa, soybean, white clover and red clover provides a built-in biological function for these plants. Seed treatments and inoculants to enhance this ability have also been used for decades.

With the biological boom in recent years, however, there are now dozens of these products on the market, often creating confusion and skepticism for farmers and agronomists alike. To help simplify this information overload, Imhoff said these products can generally be grouped under three main categories:

Plant growth regulators

These hormone-based products influence plant development through compounds such as auxins, cytokinins and gibberellins. PGR effectiveness varies widely, Imhoff noted, because their performance is highly dependent on crop health and environmental conditions. A product meant to encourage root growth, for example, may fall short if the plant lacks sufficient phosphorus to build those roots or lacks potassium to move water into the roots.

“This illustrates that sound fertility programs are—and will always be—the backbone of a crop,” Imhoff said. “Taking that away to put on a biological is like asking a bank to function without money.”

Beneficial microbes

This category includes living bacteria or fungi that support nutrient availability and soil health. Among the most well-known options are nitrogen-fixing bacteria that convert atmospheric N to plant-available nitrogen, similar to the naturally occurring processes in legumes.

This category includes living bacteria or fungi that support nutrient availability and soil health. Among the most well-known options are nitrogen-fixing bacteria that convert atmospheric N to plant-available nitrogen, similar to the naturally occurring processes in legumes.

“Most growers are familiar with the symbiotic association between Bradyrhizobium and soybean that leads to nodule formation,” Sible said. “What has changed is the discovery of soil microbes that can fix N in the rhizosphere of grass crops like corn, wheat or sorghum. Rather than developing nodules, these bacteria live along the root and feed on the root exudates. Products containing these microbes are marketed with the promise of providing plants with N, thereby allowing for a significant reduction in the need for fertilizer N inputs. These claims, however, are hard to prove.”

Other products in this category include phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria that aim to increase the amount of plant-available P in the soil, mycorrhizal fungi that aim to extend plant root systems for better nutrient uptake, and residue decomposers that help break down dead organic plant matter in the field.

However, there’s one major limitation of these types of products, Imhoff said: it’s difficult to keep living microbes viable outside of their natural soil environment.

“The use of beneficial microbes is hard to perfect when it comes to formulation and application method,” Imhoff explained. “A living microbe is difficult to keep in a static state without already having a system in place. Spore-forming bacteria show better promise. These spores can be stored much easier than other microbes and for much longer periods.”

Biostimulants

Unlike microbial products, biostimulants are non-living materials derived from biological sources. These include enzymes/phosphatases, which increase the availability of organic nutrients in soils; humic and fulvic acids that chelate soil cations to keep phosphorus available and supply micronutrients such as zinc, as well as feed microbes and stimulate root zones; marine extracts, which can mitigate drought stress when foliar-applied or promote root growth and soil microbial activity when applied to soil; and sugars that provide a direct energy source for microbes when soil-applied or stimulate the plant to mitigate stress when used in a foliar application.

“In our research, biostimulants have shown to deliver the most consistent results,” Imhoff said. “These products store well, mix easily with common applications and can be used across multiple crops.”

Because the ambiguous space of biologicals makes it difficult to find trusted, independent data, Imhoff said MFA has invested significant time and resources to evaluate various products under real-world field conditions. Over the past five years, MFA agronomists have looked at how biologicals can be applied in practical situations and conducted trials to truly understand how they work.

MFA’s small-plot studies from 2021 to 2025 included 322 different biological treatment combinations, representing variations in rates, timings, application methods, crop types and formulations. (See Figure 1). The results were eye-opening, Imhoff said. Only 10 of the 322 treatments—just 3%—delivered statistically significant yield increases compared to the untreated check. And no single product accounted for all those wins. Instead, the positive outcomes were scattered and hard to reproduce.

“Coming from a research agronomist, these findings reinforce how inconsistent biological responses can be,” Imhoff said. “Some products may show a positive trend in one crop, at one timing, at one location—but they haven’t shown enough repeatable, field-level consistency for us to make sound recommendations to growers who need a return on their investment.”

Large-scale trials have echoed the same message. Even though many biologicals can demonstrate plant responses in greenhouse or laboratory conditions—such as increased enzyme activity, better nodulation or improved root development—Imhoff said the challenge is getting consistent results across the variability of real farm fields.

“Our goal is to find products that complement the agronomic foundation we already have in place,” he said. “Biologicals should be viewed as tools to enhance existing programs, not shortcuts. We’re looking for consistent, reliable performance that helps farmers capture more of the fertility they’re already applying.”

Several products MFA has evaluated have shown enough benefit in root mass or early plant development to be adopted as recommended seed treatments. But consistent yield gains remain elusive, Imhoff said.

“In the future, we will continue efforts to test biological products,” he said. “We are still searching to find a product that can scale up to the field level and provide a stable response under repeatable conditions for our customers.”

As this sector continues to evolve, Sible said he expects that some of these products will separate themselves from the pack and prove to be another tool in the management box to improve crop yields. For now, as farmers consider biologicals, a clear goal should drive decision making, he added.

“With extreme weather events becoming more frequent and less predictable, the potential of biostimulants is likely to grow, and with proper understanding and placement, we believe that they can benefit crop production,” Sible said. “If you have interest in trying one of these products on the farm, the first step is to identify whether there’s a need and then ensure the product you select is the right tool for the job. Don’t force the biological into your system. Find the reason, and then go find the product.”

TOP CAPTION: MFA Research Agronomist Garrett Imhoff supplied this summary of MFA’s in-house studies of biologicals from 2021 to 2025. Overall, only 10 trials—3%—had a measurable yield gain different from the untreated plot. And multiple products make up that 3%, meaning that results are inconsistent and hard to replicate, Imhoff explained. GRAPHIC CAPTION: Whether applied to the plant, in the ground or on the seed, biological products have emerged as a fast-growing segment in agricultural inputs. But results often vary from claims, and MFA researchers and agronomists are helping growers make sense of the market.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE DEC 2025 / JAN 2026 TODAY'S FARMER MAGAZINE